Dancing Robots: Why are they so creepy?

Understanding the uncanny valley effect

By Olivia Higgins

From left to right: Atlas, Spot and Atlas dancing arguably better than us humans.

(Source: Youtube/Boston Dynamics, 2020)

When you watch these realistic robots dancing, chances are you might find it highly entertaining, or the polar opposite – creepy and disturbing. However, when asked why you find this unsettling, you may not be able to pinpoint exactly why. A common response is that the supposedly inanimate robot is simultaneously both fake and hyper human-like, without having physical human features. This confusion between what’s clearly unreal and lifelike disrupts the logical categorization of the brain – popularly known as the Uncanny Valley Effect (UVE).

Roboticist Masahiro Mori coined the term in the 1970s when he discovered that humans responded well to robots that interacted like humans, yet tense feelings increased as the robot became more humanlike. The inverse reaction was a window to further explore and potentially improve human-robot interaction.

In the case of Atlas (pictured above) and Spot (the yellow doglike robot), they were created to display and pursue humanlike movements to assimilate and be used in everyday society. Spot was “employed” by the Singapore government as a way to announce COVID safety measures and enforce social-distancing rules in bigger parks or streets. Atlas, on the other hand, was made for search-and-rescue missions. And now they both have one thing in common: dancing better than most humans.

Passersby amused by the robot dog Spot, as he roamed around parks to tell people to stay home at the start of the pandemic.

(Source: Singapore Government, 2020)

The viral video by Boston Dynamics.

(Source: Youtube/Boston Dynamics, 2020)

According to engineers at Boston Dynamics, the initial purpose of creating robots with the ability to dance was to test the robustness of the hardware. Instead, with 29 million views and counting, they inadvertently created viral superstars.

Published at the end of 2020, viewers tended to react positively to the viral video, expressing views such as “refreshing” and “comical” to describe the robots. However, as the dance moves started to become more intricate later in the video, the robots seeming to have minds of their own, viewers tended to express increased disconcertion - a clear example of UVE, condensed into the space of a 3-minute video.

From humble beginnings as an experiment to a viral video bringing superstardom, demand and interest in the robots dramatically peaked online, according to Boston Dynamics.

Both robots can now be purchased online for up to 75,000 USD – that is if you can handle a synthetic “human” in your house, of course. Some might actually regard Spot as being more creepy than Atlas as the mind is unable to fully determine what it is.

Familiarity coming from an unfamiliar place

The reason why such objects make us uncomfortable is rooted in core survival traits. We constantly try to make sense of the world around us through categorization so we are able to determine what is a real threat and what is not. Robots that are hard to interpret send the mind into overdrive in trying to figure out, alluding to the height of the UVE. It is scary because its humanlike traits are familiar yet it comes from an unfamiliar place, disrupting the internal worldview.

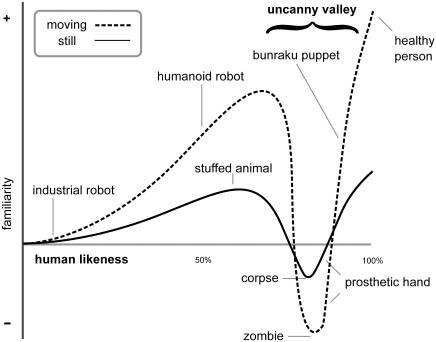

Graph demonstrating users’ reactivity and familiarity with different objects.

(Source: Masahiro Mori, 2012)

Graph demonstrating users’ increased tension to moving objects (i.e. dancing robots).

(Source: Masahiro Mori, 2012)

The dip in the figure above represents the “uncanny valley”. A robot is not considered “creepy” by virtue of being a robot, since it is clearly perceived as mechanical and artificial. However, once the mechanical robot starts to possess social capacities that are close to human interaction, like Sonny in I, Robot, that’s when the disconcertion starts. Or in the case of Spot, it is not creepy for being more human-like but rather, unfamiliar and unpredictable.

Sonny in iRobot, the only robot that possessed human emotions like empathy and anger.

(Source: I, Robot Movie)

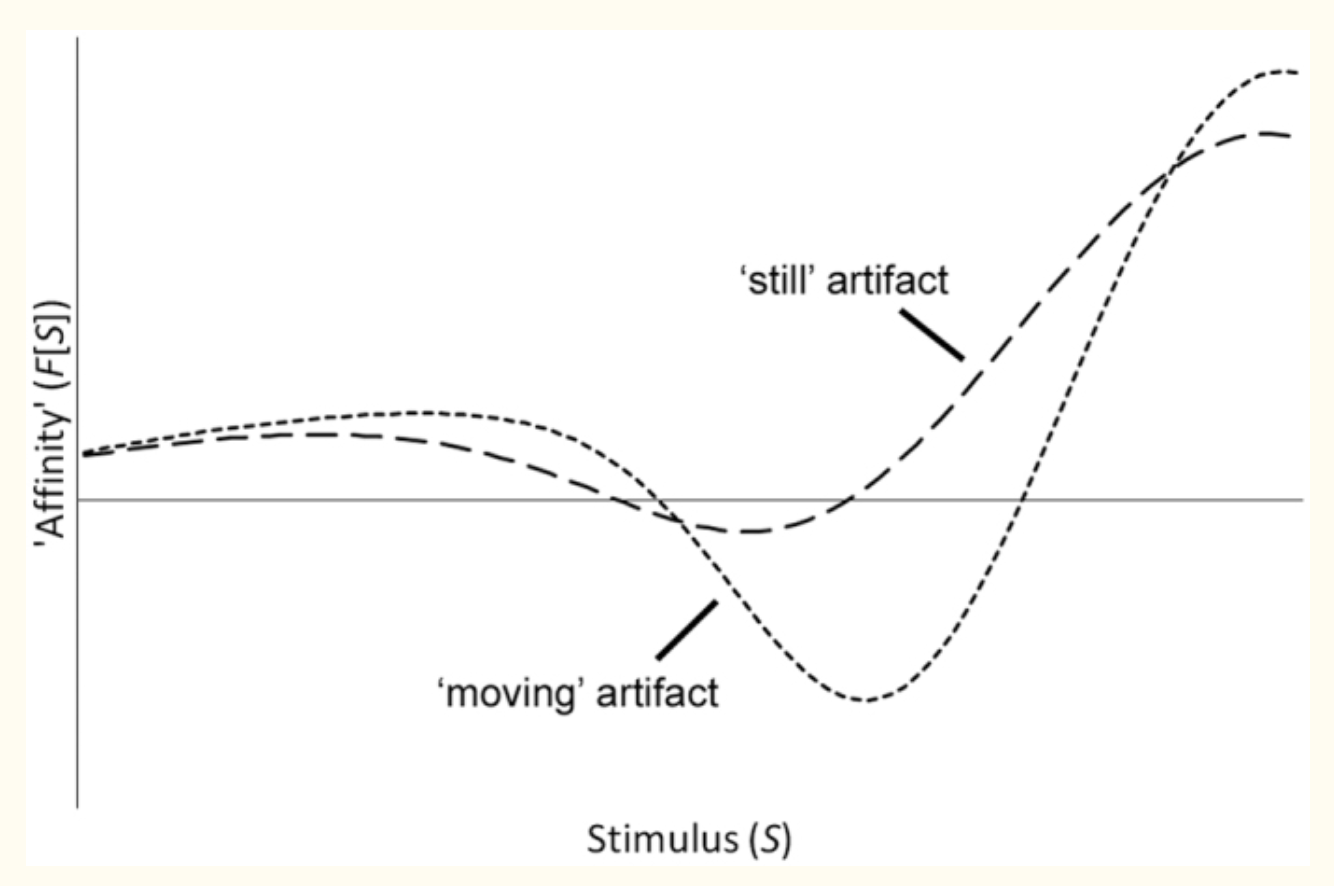

Another key aspect of Mori's original uncanny valley hypothesis was that '“a moving humanlike artifact could be perceived as being more uncanny than the corresponding still humanlike artifact” – reaffirming that you are not odd for finding those dancing robots creepy.

Graph demonstrating users’ increasing tension with the introduction of stimuli.

(Source: Masahiro Mori, 2012)

What was also a highly interesting and relevant find was how perceptual tension (graph above) - the anxiety levels related to how a user interprets the robot object - increased when the object was moving. The higher the level of movement, the more the user or viewer would turn away or ask to stop. Such findings may coincide with how Boston Dynamics can improve their robots to be more functional as part of society.

Robots as “pets” or enemies, the outsider

Some academics in the field believe UVE stems from an inanimate object resembling something that is “dead” or “rejected”. In the case of the social distancing robot Spot, people on Reddit forums online have referred to it as a mix between a mosquito and a dog – labeling it as “weird” or completely “dystopian”. Again, the mental confusion of not being able to subconsciously categorize the shape, form, and function of the robot makes it uncomfortable as an immediate interpretation.

To improve the human-machine interaction, roboticists are driven by one sole focus: the human reaction to their product. Do humans listen to the cues of the robot, or are they more distracted and scared? Mori’s research, coupled with some contemporary works (hyperlink), concludes that the more functional and “cute” the robot looks, the better the audience reception. One example is a cleaning robot designed and manufactured by Singaporean company LionsBot International. In general, people reacted more positively towards this robot compared to Spot, as it was seen as more vulnerable and as a pet. The smiling human face may also help, but strip these back, and underneath they are made up of the same nuts, bolts, and computer chips.

A robot cleaner roams around Singapore Changi Airport, one of the busiest airports in the world (pre-COVID, of course).

(Source: LionsBot International Pte Ltd, 2019)

Studies on social robotics reveal that people react to robots if they perceive them as worthy of being moral. This could mean people might perceive a robot to be similar to their dog or another animal, or as tools – making them highly incapable of inflicting damage. There are several factors involved in how they form an impression of a robot – how they act, move, talk, and level of perceived autonomous nature. Interestingly, in an experiment with soldiers who lost their bomb-dismantling robot – they chose to have the same robot fixed instead of having a replacement, indicating some form of ‘attachment’. The initial relationship formation stage between human and robot is where the future of successful human-robot assimilation begins.

A U.S. Soldier walks his robot dog.

(Source: US Air Force, 2020)

Using UVE to improve human-robot interaction

It is crucial to understand the underlying responses and concerns of UVE as it allows for constant improvements in the social interaction of humans and robots. The key factor here is assimilation with society, following great growth towards Industry 4.0. Hanson Robotics, a Hong Kong-based company that specialises in social robotics, is fast-tracking its production in 2021 with four key robots. Their most popular robot, Sophia, has appeared on numerous shows and even hosts her own live stream – arguably a primary example of UVE as her highly intelligent, witty and sometimes sarcastic remarks can be very uncomfortable for some.

Sophia is seemingly the epitome of what a modern social robot would look like and used to interact with people who have communication, social anxiety disorders yet, she is ironically still rejected for the sole purpose she was created. How can her likeability be improved in terms of hardware and software to be more “accepted” by humans?

Sophia, the Social Robot, has a substantial following on social media and was made the first Robot Citizen.

(Source: Hanson Robotics, 2019)

To answer this question, it is then crucial to look at the fundamental aspects of UVE to get to the core of what exactly makes us creeped out so that improvements can be made to take human-robot interaction to the next level.

In the aforementioned research experiments, researchers also tested whether humans have moral feelings like empathy towards robots depending on their appearance. This begs the question – do users really want a human-like robot? If so, what threshold of “human” are we willing to accept?

The UVE is crucial in helping us understand the roots as to what it means to be human. When a created object starts to shake that notion and possesses human traits of its own, it opens the possibilities for more discussion into how humans and robots can best interact to improve society. It starts with more analysis and education in both the societal and philosophical aspects of being human and ethical programming, robot-creation.

So we’ve looked at the multifunctional robots (Atlas and Spot), social robots (Sophia), and tools-based robots (cleaners and military dogs) and how each category evokes different levels of societal acceptance. This analysis tugs at a fundamental aspect of human-robot interaction on how we find these inanimate objects less threatening. It is also worthy to look at how UVE can help us in the creation of future super-intelligent systems and making them an added value rather than a distraction or deterrence to our human species.

In the upcoming second part of this article, we will explore the role of social robots and review analysis on their social integration.

Edited by J.R.C.